Source: VOA

Michael Lipin

August 31, 2014 8:30 AM

Chicago's Chinatown at Chinese New Year, February 17, 2013

WASHINGTON—

Defining ethnic groups by race creates problems because doing so is largely a subjective exercise. And such definitions are made by outsiders. For example, it was Whites who created the “Negro” race label to homogenize the multiple ethnic groups they conquered in Africa.

Asian Americans suffer from similar definitions. The larger American society tends to lump ethnic Asians together because of its inability to make distinctions between ethnic Cambodians, Chinese, Koreans and Vietnamese, for example, despite obvious differences in linguistic heritage, religious affiliations and even physical traits.

The need to group separate ethnicities is what sociologists call “racial lumping.” In this second of three reports on U.S. public attitudes toward Chinese Americans, VOA highlights the impact of "lumping" on Chinese Americans.

Also in this series, VOA examines two other common stereotypes of Chinese Americans: perceptions of them as "model" minority citizens and perpetual "foreigners" in the United States. – Editor

Why lumping is a problemSocial commentators in the United States say the public has shown a persistent tendency to label Chinese Americans as part of a generic Asian ethnic group in recent years, creating problems for the country's rapidly growing Asian communities.

The observers say Americans typically "lump" Chinese Americans who have a "successful" public image in the same group as other ethnic Asian citizens whose livelihood struggles are little understood. They say such "lumping" has made U.S. society ignorant to hardships suffered by all of its Asian minorities. It also has prompted some ethnic Asian communities to join forces to help their members overcome such struggles.

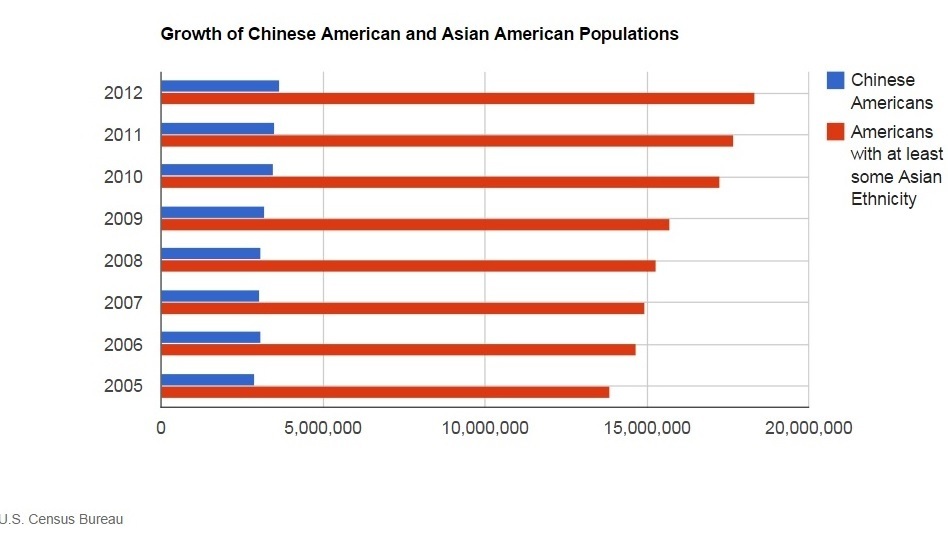

While Chinese Americans represent the largest group of Americans with Asian roots, they account for just 20% of all Asian Americans. Figures for both segments of the population have risen sharply in the past decade.

Ignorance lingers

Ignorance lingersThe last major survey of American opinion about ethnic Chinese U.S. citizens found that the majority of the general population "cannot make meaningful distinctions between Chinese Americans and Asian Americans in general."

The 2009 report by the Committee of 100, a New York-based organization of prominent Chinese Americans, said the pervasiveness of Asian American "lumping" in public opinion was the same as in its earlier 2001 survey.

A contributor to the 2009 study, Chinese American rights activist and former journalist Helen Zia, says "lumping" remains common in 2014.

"The public's lack of consciousness about who we are, where we come from, and how we are not all the same, is pretty much stuck where it's been," Zia says. "It’s like a broken record."

Charles Gallagher, a sociology professor at LaSalle University in Philadelphia, says many Americans are oblivious to the cultural, linguistic and historical differences between the country's Asian ethnic groups.

"Most whites and blacks think all Asian Americans go to (prestigious universities like) Stanford and Yale, are good in math, and own shops where they make lots of money," Gallagher says.

The Committee of 100's 2009 survey found that 57 percent of American respondents believe Asian Americans "often or always achieve a higher degree of overall success than other Americans." It said those perceptions were unchanged from 2001.

Highlighting the true pictureGallagher says that in reality, many Chinese and other Asian Americans are struggling financially, live in poor neighborhoods and lack sufficient health care.

Street musician in Manhattan Chinatown, New York City (October 2013)

"Those Asian Americans do not have the means to achieve the American dream. They are in jobs that they cannot advance from, and their children are going to face the same situation," he says.

Gallagher says Cambodian and Hmong Americans have particularly high rates of poverty, but their plight gets little coverage in the U.S. media.

"As a nation we are obsessed with focusing on historic inequalities such as those involving whites and blacks, and we don't like to talk about other ethnic groups," he says. "When it comes to Asian groups, the media conversation is about "model" minority success stories, but that does not give people a full understanding of the huge variety of experiences that Asian Americans have."

Some Asian minority groups in the United States have responded to racial "lumping" by creating joint organizations to advance the well-being of their communities.

Gallagher says organizations such as OCA - Asian Pacific American Advocates and Asian Pacific American Legal Resource Center (APALRC) identify themselves as "Asian American" because that is the label that most Americans use for them anyway.

Children in Chicago 'graduate' from a Chinese American Service League program of bilingual and bicultural affordable daycare on August 22, 2013

He says Chinese, Filipino, Indian, Korean and other Asian American communities also realize that they each represent only a tiny percentage of the population of their towns and cities.

"They found themselves in a situation in which they were not going to get any resources from the city hall pie. But, by coming together, they have strength in numbers and more leverage with firefighters, police and schools to achieve the political needs of their communities."

William Wei, a Chinese American professor of history at the University of Colorado in Boulder, says another response of Asian minorities to the "lumping" stereotype has been the development of educational programs for Asian American studies.

"These programs have been at the forefront of spreading knowledge about Asian American history and culture," Wei says. "They have been very important in recent decades, because they produced Asian American scholarship that eventually made its way into mainstream U.S. education."

One organization that promotes such scholarship is the Association for Asian American Studies. Founded in 1979, its list of universities with Asian American studies courses and departments has grown into the dozens.

Other forms of self-identification

While some U.S. citizens with Chinese and other Asian origins have embraced the "Asian American" label, most have not.

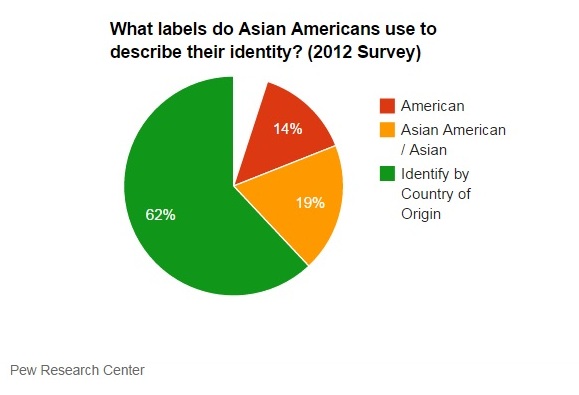

A 2012 study by U.S. opinion poll organization Pew Research Center showed that only 19 percent of Asian Americans actually describe themselves as "Asian American" or "Asian."

It said 62 percent of Americans with Asian ethnicity most often described themselves by their country of origin, such as "Chinese" or "Chinese American," "Vietnamese" or "Vietnamese American," and so on. Another 14 percent said they simply call themselves "American."

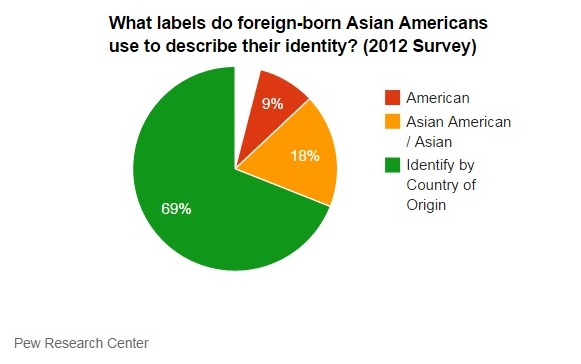

Pew found that among Asian Americans who were born abroad and immigrated to the United States, the rate of self-identification by country of origin was higher, at 69 percent.

Frank H. Wu, a Chinese American commentator who heads the University of California Hastings College of the Law, says those findings do not surprise him.

"People in Asia don't identify with pan-Asian sensibilities," Wu says. "The notion of a 'united Asia' is associated with imperialism or idealism. People identify much more specifically as Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Filipino or Indian and so on. They don't say, 'I'm an Asian'."

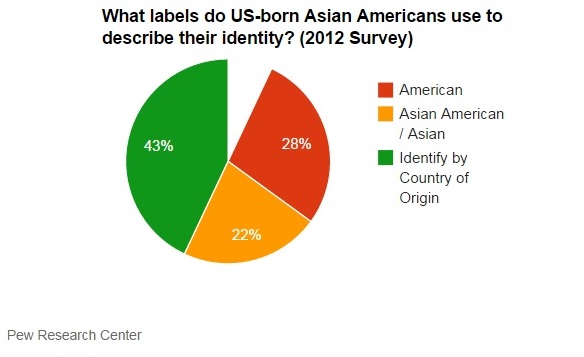

Among U.S.-born Americans of Asian origin, Pew said the proportion who prefer to call themselves "American" rose to 28 percent, while the rate of self-identification by country of origin fell to 43 percent.

Sociologist Gallagher says Chinese and other Asian Americans whose families have been in the United States for one or more generations have assimilated into American culture much faster than other ethnic minorities.

"If you are a third or fourth-generation Asian American, you do not necessarily think and behave like people from your ancestral homeland," Gallagher says.

"You don't have that immigrant experience any longer. You're an 'American'."

But will immigrants from China and their descendants ever escape the "Asian” label that is so engrained in society?

It is conceivable. When the U.S. Census Bureau makes racial distinctions, it says they are a reflection of the country's prevailing social attitudes, rather than an attempt to define race "biologically, anthropologically, or genetically."

Historically, many Americans once labeled Irish, Italian and Jewish immigrants as non-White races. Today, the U.S. Census Bureau gives individuals the freedom to identify themselves as they wish.

Graphics by Idrees Ali. Additional research by Haleema Shah.

http://www.voanews.com/content/us-publics-labeling-of-chinese-americans-as-asians-poses-challenges/1955178.html[ 此帖被卡拉在09-02-2014 18:00重新编辑 ]